|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Humans may exchange pictures of plants and animals to communicate emotion. In this case a plant or animal is used as a symbol of a particular emotion based on the sender’s and receiver’s shared association of a plant or animal with that emotion. For example, a greeting card featuring a picture of a plant associated with love (e.g., a red rose) may be exchanged to communicate that feeling.

1.2 Species and Stylistic Variation Humans around the world draw plants and animals for the same purposes but the species chosen for depiction and the drawing-style are both culture-dependent. It may be quite a challenge for a viewer from one culture to understand and appreciate pictures drawn by artists of another culture. This challenge is especially great for westerners (e.g., Europeans, North Americans) when viewing plant-animal pictures from the far-east (e.g., Japan, China). Not only are the species depicted likely to be unfamiliar because of their restricted geographic range but the traditional philosophy of art is also very different, resulting in large stylistic differences between east and west. The western artist typically aims to copy the external features of plants and animals with great accuracy thereby creating a very realistic picture (Sullivan, 1973). In contrast, the far-eastern artist aims to reveal the inner spirit of the plant or animal instead of its physical appearance (Rowland, 1954). Some external features are either ignored or distorted to help create a sense of movement and action which reveals inner spirit. Spirit is emphasized over form because the artist is often interested in using the plant-animal picture as a vehicle to reveal his own spirit and emotional state. Far-eastern religions such as Buddhism and Shintō teach that all plants and animals are endowed with a spirit, not just humans (Saito, 1985). By depicting the spirit of other organisms an artist can reveal his own spirit as well. When this link between humans and other organisms is extended to include emotion, plants and animals become useful tools to express and communicate human emotion in pictorial form. Far-eastern artists make extensive use of plants and animals as symbols of human emotion (Narazaki, 1970). Fewer western artists are likely to use a plant or animal to help reveal human spirit or to communicate human emotion because most westerners do not have a strong belief in the spiritual equality of humans, plants and other animals. The dominant western religion of Christianity has taught them that plants and animals are inferior to humans in both body and spirit (Sullivan, 1973). Capturing the external features of plants and animals rather than spirit has been the goal of most western artists.

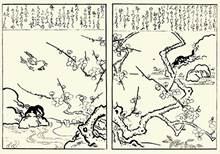

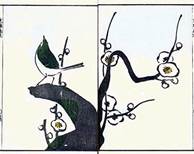

For westerners unfamiliar with the far-east an encounter with a selection of far-eastern plant-animal pictures (Figure 1.1) is likely to raise the following three questions: 1. What are the names of the plant and animal species and why were these particular species chosen as subjects? Neither the plant (Prunus mume) nor the bird (Cettia diphone) in Figure 1 would likely be familiar to a western viewer because both are native to eastern Asia. In contrast, they would be well known to far-eastern viewers, especially the Japanese, who use them as symbols for both human emotion and the start of the spring season (Otto and Holbrook, 1902).

2. Why were the plant and animal drawn using a particular style and why did artists choose different styles? A western viewer conditioned to the use of a realistic drawing style for plants and animals would be surprised by the lack of realism apparent in most of the pictures in Figure 1. Understanding the traditional far-eastern philosophy of art would make this lack of realism less surprising. Style changes historically in all cultures. This set of nine pictures drawn between 1683 and the late 1900s largely reflects historical change in style due to changing social conditions, technology, and foreign artistic influences. The education of most western viewers is unlikely to include enough far-eastern history to understand this stylistic variation without further reading.

3. Who is the artist and when was the picture drawn? Until recently, far-eastern artists have not used the roman alphabet to sign or date their pictures. Consequently, most western viewer would have difficulty reading a signature, seal or date appearing on a far-eastern picture. In some cases none of this information appears on the picture. Picture-books may include the artist’s name and publication date only on the end page. When these books are taken apart by dealers to sell the pictures individually the purchaser no longer has access to information about the artist and date of publication. Six pictures in Figure 1 (i.e., Moronobu, Gyokusuisai, Minwa, Soken, Yoshiharu, Gahō) come from books.

Finding answers to these three questions would be a challenge for the westerner viewer because far-eastern pictures of plants and animals have not been the subject of many art history books written in the roman alphabet. Currently there is no reference book which addresses all three questions. As a first step towards filling this gap this book provides a guide to the what (species), how (style), who (artist), when (history), and why of a subset of far-eastern plant-animal pictures; namely, Japanese woodblock prints of flowers and birds.

1.5 Japanese Woodblock Prints of Flowers and Birds Only a subset of far-eastern plant-animal pictures is considered here because the complete set is overwhelmingly large. This particular subset was chosen because it is likely to be among the first encountered by westerners and also of most interest. A printed picture has multiple copies making it more likely to be seen and owned than a painting which has no copies. Woodblock printing is the traditional means of producing both printed pictures and books in the far-east. In this form of printing the outline of an object is created on a block of wood by chiseling away unwanted surrounding areas leaving the outline raised in relief above the wood’s surface. Ink is applied to the raised outline, followed by a piece of paper, and the back of the paper is rubbed to transfer ink to paper. To create a multi-colored print the piece of paper is placed sequentially on a series of wooden blocks each carved and inked differently to show a particular portion of the picture design. In western countries woodblock printing has been used much less than other methods such as intaglio (e.g., etching, engraving), lithography, and screenprinting. Consequently, far-eastern woodblock prints are of special interest to westerners because they are both novel and exotic. Japan produced far more plant-animal woodblock prints than any other far-eastern country. The Japanese developed woodblock printing to a fine art and used it almost exclusively between the 1600s and the late 1800s (Kornicki, 2001). At that point intaglio and photography-based printing techniques replaced woodblock printing for everyday use because those methods were more cost-effective for large print runs. Some artists preferred to continue using woodblock printing for the effect it creates and do so today (Ajioka, 2000). Japanese woodblock prints of plants and animals are most likely to feature a plant with flowers (or fruits) in combination with a bird (henceforth called flower-bird print). In a sample of 8873 pictures from my personal collection of Japanese plant-animal images, plants were shown with flowers or fruits 63% of the time versus 37% without flowers or fruits and a bird was the animal subject 82% of the time compared to only 18% for all other types of animals combined. The bright colors of flowers and fruits understandably make them a popular subject. Birds are also highly visible which likely contributes to their popularity. Other types of animals are less visible because of their aquatic or semi-aquatic habitat (e.g, fish, crustaceans, amphibians), their nocturnal habits and fear of humans (e.g., mammals, reptiles) or their small size (e.g., insects). Religions around the world also give birds a special significance as the carrier of both gods and the human soul to heaven (Armstrong, 1975).

Answers to questions about the what, how, who, when and why of Japanese flower-bird woodblock prints are presented in chapters 2 through 4. These answers are based on an examination and analysis of 5393 flower-bird pictures from my personal collection of Japanese woodblock images. Chapter 2 focuses on the flower and bird subjects of a picture to address the question ‘what are the names of the flower and bird species and why were these particular species chosen as subjects?’. The answer includes flower and bird names, sample pictures and characteristics which likely affected their chances of being chosen as a subject. Chapter 3 deals with artistic style to address the question ‘why were the flower and bird drawn using a particular style and why did artists choose different styles?’. To answer this question distinguishing features of different stylistic schools are presented and their history of use is interpreted in terms of prevailing social conditions, cultural traditions and foreign artistic influences. Chapter 4 considers book publishers, editors and artists of bird-flower pictures to address the question ‘who is the artist and when was the picture drawn?’. The answer includes the individuals’ names and period of activity.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Next Chapter or Back to Guides

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||